*

The sea's dappled and glimmering, silk-smooth.

Dolphin conditions, we say

hoping that every

dark curve of wave

might instead be a sinewy back

Mid-ocean a small finch flits past, many miles from land; and then an hour later another. I guess they're on migration. I feel a moment's fear for their fragility, their distance from flock and land.

In another life, the life of a scientist, bird migration would have been my subject of choice. It is a wonder, a little miracle, the fact of bird migration.

Tell me how swallows navigate home

over and over

those few grams

against all the implacable ocean

(from Looking For Icarus, Roselle Angwin 2005, bluechrome)

Some say there's a kind of compass/lodestone in the bird's brain attuned to magnetic north. Some say birds navigate according to moon and stars. I've also heard, astonishingly, from a physicist dowser, that here in Britain waves crashing on the Western Atlantic seaboard send shockwaves through bedrock and the seabed that emerge as, I believe, infrasound, or at any rate as electromagnetic waves, high in the Ural mountains – and that wild geese navigate by these waves.

What's more, there is a deep knowing in the bird about where it needs to go, what constitutes home.

I find these things extraordinarily inspiring; and moving, too. A lone recently-fledged swallow, merely two or three months old, from a late brood here in England can find its way to where it needs to be by itself, for instance, despite that being another continent to which it has never travelled. And back again!

And here mid-ocean I'm aware that ships, and ferries like the one on which I'm sitting, save the lives of many exhausted migrating birds each year simply by offering temporary landing spots.

I'm on a 3-day migration to a favourite place: the magical Foret de Huelgoat in Brittany.

Brittany of course has much in common topologically (do I mean topographically?) as well as linguistically and culturally with the Celtic lands of Britain, especially the Western Celtic fringes. I read a very little medieval Welsh (part of my degree) and my father speaks some Cornish, so I can guess at some of the words and place names here. The Breton language is P-Celtic, or Brythonic Celtic, as are Welsh, Cornish and Manx (and maybe Galician); Scottish and Irish Gaelic tongues have Q-Celtic, or Goidelic, roots in common. In Welsh the word for 'wood' is 'coed'. Huelgoat incorporates the Breton word for 'wood', also 'coed' or 'coët', in its suffix 'goat' (consonants often mutate in the Brythonic languages depending on preceding or succeeding vowels). (If I ever knew what 'Huel' meant I've forgotten.)

Further south is the bigger and wonderful Foret de Broceliande, the Celtic enchanted forest of the Knights of the Round Table, Merlin the Sorcerer ('sorcerer' comes from the French words 'sourcier', one who divines for water), Vivianne, Morgana, Excalibur etc.

Huelgoat Forest is a much more modest but still utterly magical place, with its share of legends and Arthurian associations, as well as its magnificent long walks, one of our reasons for being here.

It reminds me of various spots on my local Dartmoor, from the moss-bedecked boulders with almost-fused little old oaks of the remaining ancient woodland to the deep gorges of Lydford with their 'devils' bowls' and roaring waterfalls. Here everything is larger-scale, and very lush. In the photo above, that opening in the rocks is man-sized; the path goes through it.

The path starts at the wonderfully-named Moulin du Chaos, the other side of the small road-bridge from this fierce concentration of water:

– not far from which two swans and their brood of six cygnets are paddling tranquilly. A small group of teenage boys looks to be considering whether to dare each other to jump. I'd have said there was little chance of surviving the huge tug and rush of the waterfall the other side turmoiling through the massive boulders in the gorge. I'm relieved that they've disappeared and there's been no siren by the time we pass by an hour or two later.

At the base of the huge boulders by the moulin (mill), where their rocky feet are in the stream, so to speak, a pair of grey (ie yellow) wagtails is performing astonishing backflips and nosedives, skimming flies from the threshold of air and water. Their solitary surviving youngster is perched on a low rock right above a huge fall of water waiting to be fed, tail flipping like a clockwork toy's.

This first evening, fresh off the boat, we take the path through the rocks with their fringes of bluebells and campions under tall chestnuts and beeches, the gold-leafed oaks; wander towards La Roche Tremblante, an enormous monolithic logan stone which, reputedly, if you lean against it at exactly the right spot, should rock slightly. We fail to make it rock, and smile ruefully at each other. (There follows a small and inevitable wisecrack by TM, which I'll spare you.)

Ahead, a red squirrel bounds up into the canopy. Below, the woods are settling into their non-human life of dusk.

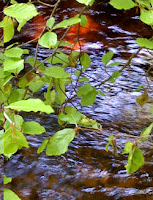

We turn back to take another track through a small alley in the town, a circular trail past the tail-race of the leat –

– to find a creperie for that excellent Breton speciality, a crêpe de

blé-noir, or buckwheat flour, with creamy wild mushrooms and a salad.

(We find it in a small smoky ancient stone front room of the family-run

Crêperie de Myrtille.)

Through the half-open door the deepening sky is shrilling with swifts. A sliver of moon is considering make herself known.

I'm content.

This is also a home.

No comments:

Post a Comment